“In basket divination, human bodies, artifacts, words, and spirits work together in symbiosis. Knowing is a spiritual, intellectual, and embodied undertaking.”[1]

Anthropologists of the early twentieth century were impressed by the intellectual agility of basket diviners. The ritual featured a man shaking a basket aggressively while various articles jostled inside. As they landed, the ritual expert interpreted the meaning of their fall for his client in a serious and reflective tone. This led researchers, most famously Victor Turner, to classify divination as a supremely cognitive symbol in contrast to more emotional rituals.[2] These scholars saw their classification of divination’s analytic emphasis as a way of intellectualizing the practice from its “primitive” setting. Yet as anthropologist Sónia Silva writes above, knowing is never just a cognitive enterprise. Indeed, divination is a means of accessing otherwise inaccessible information, but it is also a deeply spiritual and embodied practice. As Silva observed during her fieldwork in northwest Zambia, Africa, “Diviners report that they feel the truth before they see and speak it; and that they think in the head and heart.”[3]

When I set out to teach a course on ancient Jewish magic, I wanted to echo Silva’s point. The course traces the arc of divination and prophecy, spells and amulets, and magicians and exorcists from the ancient to the modern world. While we dealt with Jewish traditions, we also considered the categories of “magic” “miracle” “science” “philosophy” and the methods of knowing in the world. But rather than focus solely on cognition, I wanted to emphasize the embodied role of the ritual expert. This inspired me to bring incantation bowls into the classroom.

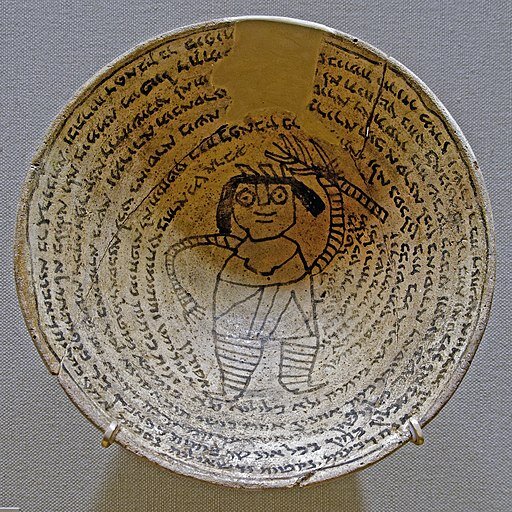

Incantation bowl with an Aramaic inscription around a demon. From Nippur, Mesopotamia 6th–7th ce. Photographer Marie-Lan Nguyen

Babylonian incantations bowls dating from the fifth to seventh centuries C.E. number in the thousands.[4] Written mostly in Jewish Aramaic, the bowls employed a variety of incantations, including Jewish legal language, to redress ills usually attributable to demonic agents.[5] The adjurations are written in ink on the inside of a concave clay bowl, sometimes including an illustration of the demon(s) addressed in the incantation. These bowls protected clients and their households from demonic agents.

It was important to me that my students see incantation bowls as more than symbols, or even just textual incantations, but as a real form of knowledge embodied in relationships between human subjects, divine beings, and material objects. Late Antiquity was a time in which gods and men routinely interacted, and experts of knowledge—of both heavenly and earthly origin—provided meaningful ritual services. This was a radically different way of inhabiting the world than for many in modernity.[6] I wanted my students to feel the clay, examine the words of their incantations, and feel the physicality of ritual knowledge and expertise.

The Process

Robin Nordmore, from the Kenyon College Craft Center, instructing on how to prepare clay for draping.

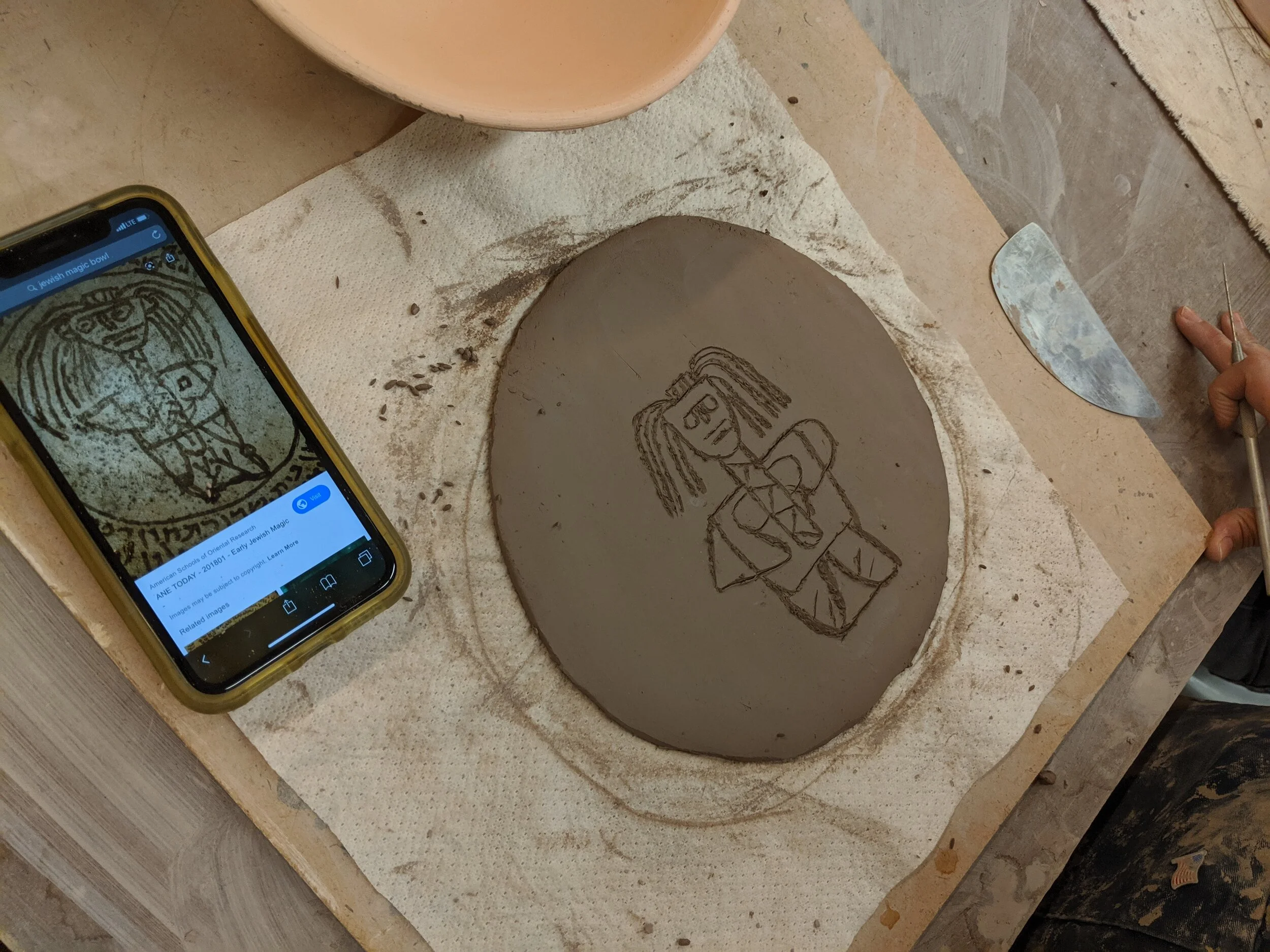

I contacted Robin Nordmoe, a pottery instructor at the Kenyon College Craft Center, and together we devised a two-part incantation bowl exercise on the construction of draped bowls and the art of transcribing text. In the first session, students cut round clay disks and inscribed the visage of their demon in the center. Students referred to photographs of surviving Babylonian incantation bowls as inspiration for their depictions. The clay disks were then draped over molds and set to dry.

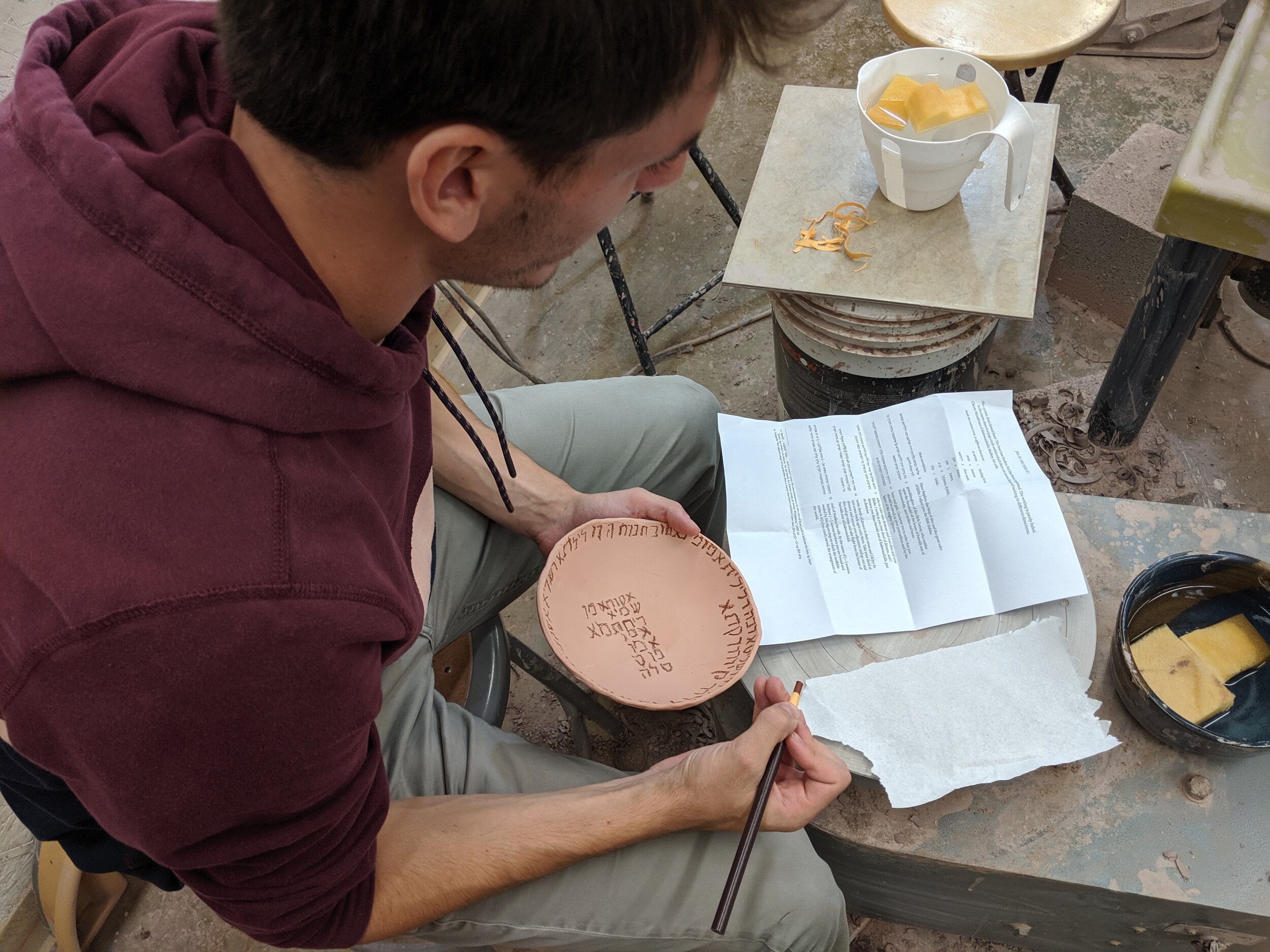

After the first round of firing, the students wrote their incantations upon the rough surface of the bowls. Using Shaul Shaked’s “Aramaic Bowl Spells” (2013) as their base, students adapted and copied existing Aramaic incantations onto their bowls. Some students were inspired to translate incantations into other languages they knew, such as Arabic and Old English. They then smoothed pigment into the crevices of the bowls in order to mimic the weathered imperfections of firing systems of late antiquity (the kiln at Kenyon is just too clean!). The last step was to seal the bowl with wax.

In the end, each student participated in the ancient craft of incantation bowl making and took home an artifact as a reflection of their class studies. My students appreciated the opportunity to get out of the classroom, try their hand at a new craft, and still feel like the activity was relevant to our learning. Throughout the process, we talked about ritual efficacy, ways of knowing in the world, and legal expertise, and religious piety in the Jewish Babylonian context. Through the making of physical bowls, my students were forced to grapple with Silva’s assertion that “[k]nowing is a spiritual, intellectual, and embodied undertaking.”

I Don’t Have a Kiln…What Now?

Kenyon College is certainly exceptional with an on-campus Craft Center with an accessible kiln for students. But! The pedagogical purpose of making incantation bowls can still be achieved in other more accessible (even remote) forms.

During the global pandemic of 2020-2021, I mailed my remote students a tub of Crayola air-dry clay (color Terra Cotta). Prior to class they shaped bowls with the clay and allowed them a few days to dry. Then in our virtual class we wrote our incantations together as we might normally. While it wasn’t quite the same as shaping the clay and firing in our campus studio, it achieved the same effect of producing material objects of ritual expertise.

Alternatively, Dr. Catherine Bonesho at UCLA devised a similar exercise but with more accessible and affordable materials. She writes:

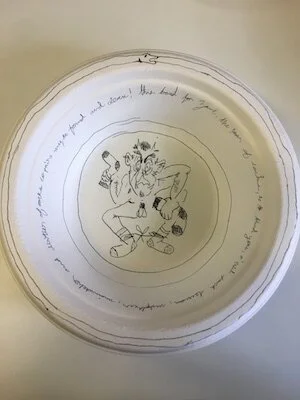

Zane Kaufmann

“For this in-class project, students were given disposable bowls to make their own renditions of magic incantation bowls after reading Rebecca Lesses, “Image and Word: Performative Ritual and Material Culture in the Aramaic Incantation Bowls.” I wanted students to think about the overall materiality of these objects and the process of inscribing the bowl with texts and objects, and the later placement of these bowls. They seemed to appreciate the hands-on exercise and had more of an appreciation for the choices people in antiquity had to make for their own protection.”

Dr. Simcha Gross at the University of Pennsylvania had his students compose their own magical handbooks based on ancient Jewish grimoire. One student provided an imaginative (reader: do not try at home) recipe for Covid-19, highlighting the nebulous boundary between magic and medicine:

"To protect oneself from contracting Coronavirus, take a solution of water, Clorox, & Hydroxychloroquine & recite LPQR & LWRS over it seven times, drink this solution every morning before leaving home & interacting with numerous strangers at crowded markets."

Read more about Gross’ exercise in this twitter thread:

Both of these ideas modify the accessibility of the activity but retain the emphasis upon hands-on student creation of material knowledge.

Krista Dalton is Assistant Professor Religious Studies at Kenyon College in Gambier, OH.

[1] Sónia Silva, “Mind, Body and Spirit in Basket Divination: An Integrative Way of Knowing” Religions 5, no. 4 (2014): 1175.

[2] Victor Turner, The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual (Cornell University Press, 1967); Revelation and Divination in Ndembu Ritual (Cornell University Press, 1975).

[3] Silva, “Mind, Body and Spirit,” 1179.

[4] For an overview, see Yuval Harari, “Jewish Magical Literature: Magical Texts and Artifacts” in Jewish Magic Before the Rise of Kabbalah.

[5] Avigail Manekin Bamberger, “Jewish legal formulae in the Aramaic incantation bowls” Aramaic Studies 13, no. 1 (2015): 69-81.

[6] Catherine Chin, “Marvelous things heard: On finding historical radiance” The Massachusetts Review 58, no. 3 (2017): 478-491.