This book draws attention to one important but neglected concept from Hellenistic literary criticism that readers—including Christians—used to organize, describe, and evaluate narrative traditions.

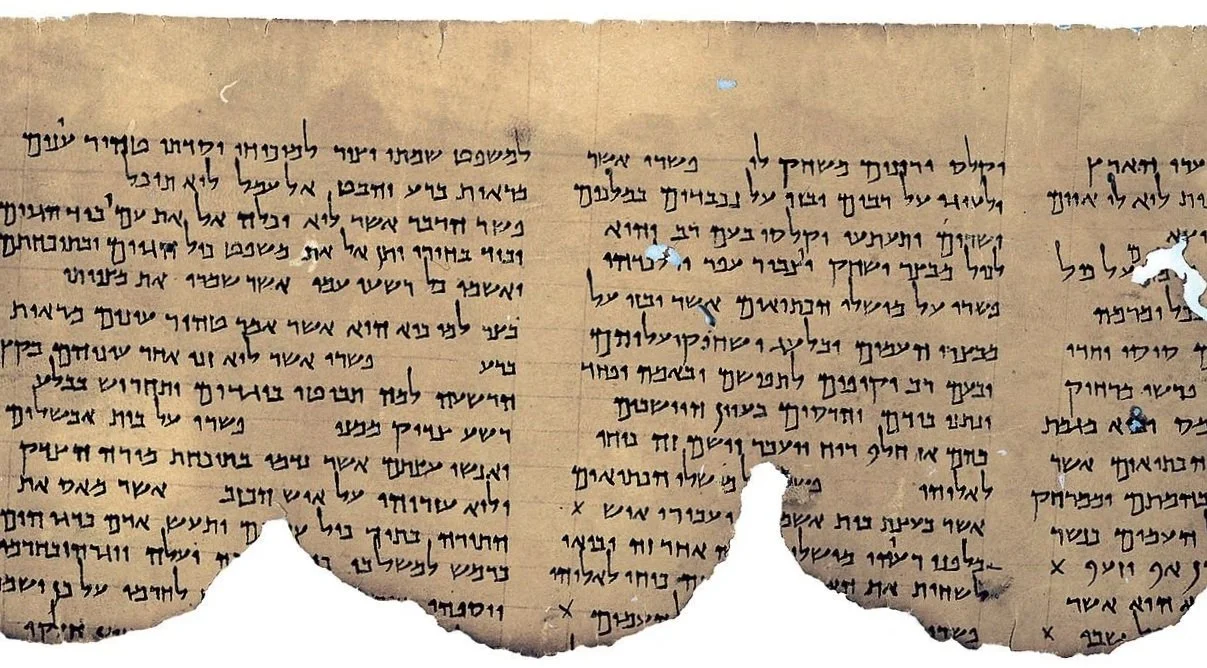

Alex P. Jassen previews his new book exploring the diverse ways social contestation and violence was perceived and imagined by the Dead Sea Scrolls Sectarians.

To expand thinking around performance and apocalypse, my project incorporates a consideration of gender to these categories. So, in this project, I am concerned with answering the question “is there such a thing as apocalyptic masculinity?”

The Aramaic Dead Sea Scrolls display an overwhelming interest in the Israelite priesthood, sacrificial cult, and Jerusalem temple. A look at the Aramaic Levi Document reveals that this interest may have to do with the shifting fortunes of the priesthood in the third century BCE.

In this study a sustained, interdisciplinary argument is offered for the presence of women in parables where they are not named or explicitly described.

The understanding that Jews engaged with a full sweep of Islamic sciences was arguably one of the earliest insights of modern Jewish historiography; indeed, medieval Jews were sometimes explicit about turning to non-Jewish sources. But scholarship has traditionally highlighted Jewish engagement with the larger world in fields other than law, such as poetry, theology, and linguistics. Building on the work of others, After Revelation recognizes that medieval Jews and Muslims structured their traditions in similar ways.

The question of how many sisters were portrayed with Jesus at the Raising of Lazarus in early Christian art has not previously been explored, and interestingly, the hypothesis that Martha was added later aligns with the number of sisters portrayed in early art of the Raising of Lazarus.

Rather than studying the History through a literary lens, my dissertation re-visualizes the texts and the relationships therein through a process of mapping – first, by understanding the city itself and its position among trading cities on the Mediterranean Sea; as I engage with data sets and digital tools to create this method of understanding, it becomes clear how the narrative thread, style, and scope of the History played a role in the text’s reception and legacy.

This position paper issues a call for editors and publishers with oversight over peer-reviewed publications of inauthentic post-2002 Dead Sea Scroll-like fragments to embark on the processes that would consider (and likely result in) retraction. By common consent, findings in the publications identified in this essay are unreliable at best; many present material subsequently deemed falsified. Retraction is the proper and justified measure to take regarding these publications in order to correct the academic record and alert any and all potential readers to the untrustworthy nature of their content.

Power in the Name contributes to this growing body of work unbeholden to the myopic strictures of materialism and (more broadly) scientism by comparatively analyzing examples of humans changing their environment (e.g., healing or hurting others) by invoking powerful divine names.

“This book plunges us deep into the social relationships that made the production of rabbinic expertise possible. Weaving together accounts of tangible material support with sites of contact between rabbis and other people, I explore how rabbinic expertise was continually enacted and challenged through social interactions.”

“Cultural difference does not condemn us to incomprehension. It forces us to go beyond our own cultural horizons in an effort to make sense of what is going on in the world of others. Ancient historians must use the mindset of a cultural anthropologist, in addition to the traditional tools of their discipline.”

The exceptional influence and popularity enjoyed by DEH from late antiquity through the Middle Ages, and its critical interface with Jewish historiography as a work both based on and source of major Jewish histories, suggest that this work is important for scholars of pre-modern Judaism and/or Christianity to know.

Catherine Hezser and Constantin Willems introduce the AHRC-DFG Collaborative UK-German Research Project in the Humanities (2023-26) on Rabbinic Civil Law in the Context of Ancient Legal History.

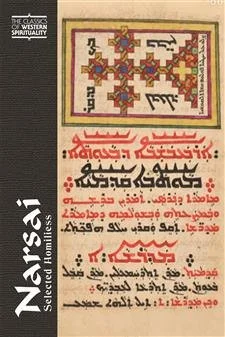

As I learned more about the literature and history of my tradition, I found myself drawn to another important author, Narsai, and wondered whether someday a similarly accessible and instructive volume might be written about him. This project has been both a dream and an aspiration ever since.

Advisory Board member Andrew Jacobs reflects upon the past 10 years of Ancient Jew Review.

Was imperial rule indeed so antithetical to local agency, or was it in fact a facilitating factor in the formation and consolidation of local elite identities? Did the Hasmoneans and their supporters really espouse such an anti-imperial political theology as is often associated with them? What would change in our understanding of emerging Judaism and the Jewish political imagination if we were to reimagine the Hasmonean period without such a heavy emphasis on Jewish national and religious identity in opposition to empire?

From the outset, I envisaged two clearly distinct books, one popular and the other more academic, one with fewer footnotes than the other.

Whereas scholarship has tended to investigate this question by analyzing the development of Jewish apocalypticism, afterlife beliefs, and theodicy during the Hellenistic and early Roman periods, my analysis of consolatory rhetoric in Hellenistic Judaism offers a more comprehensive approach.

To expand thinking around performance and apocalypse, my project incorporates a consideration of gender to these categories. So, in this project, I am concerned with answering the question “is there such a thing as apocalyptic masculinity?”

In this study a sustained, interdisciplinary argument is offered for the presence of women in parables where they are not named or explicitly described.

Rather than studying the History through a literary lens, my dissertation re-visualizes the texts and the relationships therein through a process of mapping – first, by understanding the city itself and its position among trading cities on the Mediterranean Sea; as I engage with data sets and digital tools to create this method of understanding, it becomes clear how the narrative thread, style, and scope of the History played a role in the text’s reception and legacy.

Was imperial rule indeed so antithetical to local agency, or was it in fact a facilitating factor in the formation and consolidation of local elite identities? Did the Hasmoneans and their supporters really espouse such an anti-imperial political theology as is often associated with them? What would change in our understanding of emerging Judaism and the Jewish political imagination if we were to reimagine the Hasmonean period without such a heavy emphasis on Jewish national and religious identity in opposition to empire?

The goal of this dissertation is to provide an example of what insights can be gained when emotions—in particular, disgust—are examined in an archive traditionally mined for theological and historical insights.

I wanted to make this intervention because the ubiquity of humans being described as enslaved to God or Christ is easy to miss. As Clarice Martin demonstrated in her 1990 article on womanist biblical interpretation and inclusive translation, scholars and translators have often disguised or euphemized language of enslavement because of a discomfort with acknowledging the presence of enslaved people within the pages of the Bible. I argue that the process of undoing euphemistic translation and uncovering the presence and logics of enslavement in Jewish and Christian literature does not stop with those depicted as enslaved to humans, but extends to those depicted as enslaved to deities.

Augustine drew on the central Christian idea of sacramentum—a technical but expansive concept indicating the mysterious conjoining of the sensible to the intelligible, the human to the divine—to produce a unified theory of existence that stands in contrast to the dualisms of his time.

By thinking with premodern Christians as they imagined Muslims and Jews, we can also take a reflexive look at ourselves in the present. How and why do we identify with objects, particularly those from the past?

AJR continues its #conversations series with an exchange between Daniel Caner and Erin Galgay Walsh on Caner’s book, The Rich and the Poor: Philanthropy and the Making of Christian Society in Early Byzantium

We’re talking about my recent book, The Myth of the Twelve Tribes of Israel, and it is about people who have claimed to be ancient Israel—or had that identity claimed for them—from biblical times to the present. More specifically, it is about how all these groups used the same tradition, the tradition of the twelve tribes of Israel, to fashion Israelite identities for themselves. So it’s called what it’s called because it’s about the power of this one tradition—which is what I mean when I say myth, not a false story but a powerful cultural tradition—among many different groups, starting with biblical Israel.

Why demons? Why did you choose demons to write on and what can they teach us today?

What I tried to do is carry out trauma’s movement and plurisignifcation—its constant intertextual attaching onto thing after thing after thing—by adding layer upon layer of intertextual exegetical examination, sometimes (often times?) without spending too much time in any one place.

As early Christian authors continued to build upon and intensify Roman carceral spaces they imagined a system of divine justice in which ever increasing forms of violence are sanctioned by God to elicit proper behavior.

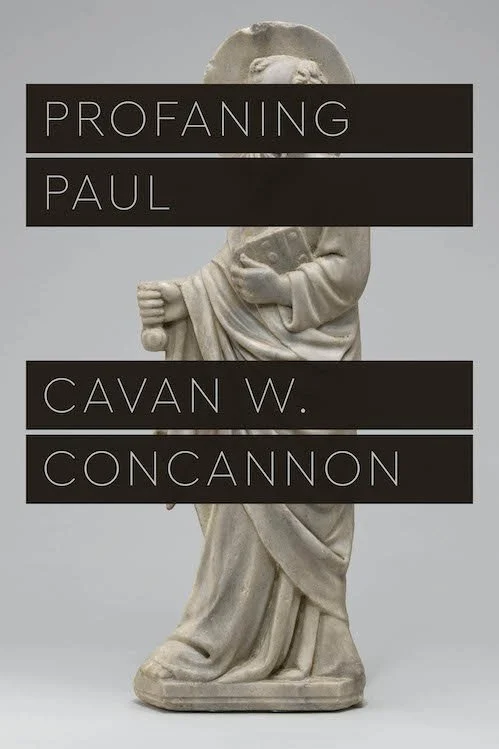

“I would like to see nondisciplinary conversations about Paul’s archive, how his writings and themes moved through western history and how that movement involved configurations and operations with other texts, institutions, and politics.”

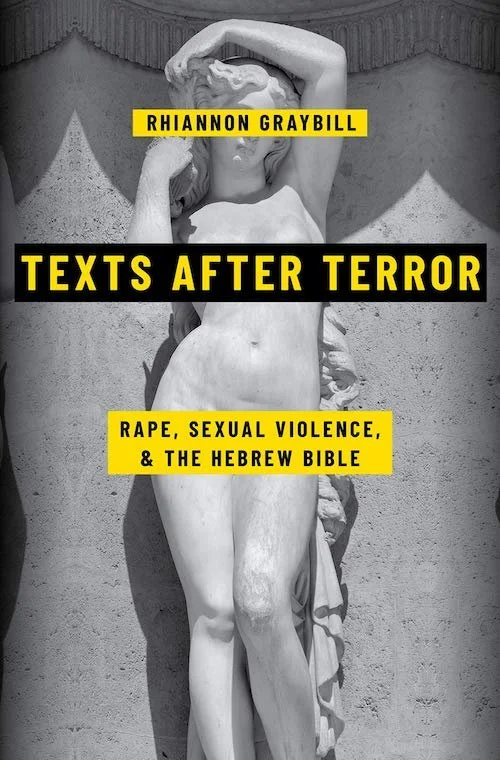

AJR continues its conversations series with an exchange between Rhiannon Graybill and Jill Hicks-Keeton on Graybill’s new book, Texts After Terror: Rape, Sexual Violence, and the Hebrew Bible (Oxford University Press, 2021).

The Aramaic Dead Sea Scrolls display an overwhelming interest in the Israelite priesthood, sacrificial cult, and Jerusalem temple. A look at the Aramaic Levi Document reveals that this interest may have to do with the shifting fortunes of the priesthood in the third century BCE.

The question of how many sisters were portrayed with Jesus at the Raising of Lazarus in early Christian art has not previously been explored, and interestingly, the hypothesis that Martha was added later aligns with the number of sisters portrayed in early art of the Raising of Lazarus.

This position paper issues a call for editors and publishers with oversight over peer-reviewed publications of inauthentic post-2002 Dead Sea Scroll-like fragments to embark on the processes that would consider (and likely result in) retraction. By common consent, findings in the publications identified in this essay are unreliable at best; many present material subsequently deemed falsified. Retraction is the proper and justified measure to take regarding these publications in order to correct the academic record and alert any and all potential readers to the untrustworthy nature of their content.

Advisory Board member Andrew Jacobs reflects upon the past 10 years of Ancient Jew Review.

In this article, I want to contextualize the term polupragmosunē as it is used in the works of other writers in the Roman imperial period (particularly Plutarch, Apuleius, Lucian, and Tertullian) and demonstrate how polupragmosunē is a key component of Diognetus’s anti-Jewish rhetoric and construction of uniquely Christian knowledge.

The ten most-read publications from Ancient Jew Review for the year 2023.

What did she want us to see and know differently? How did she want to shape us?

Dr. Steven D. Fraade wrote this article while on sabbatical in 1988. It was accepted for publication soon after, but the journal wanted substantial cuts due to the space constraints at the time. AJR is pleased to give this article a permanent home and hope it will inspire future work on this important subject.

This book draws attention to one important but neglected concept from Hellenistic literary criticism that readers—including Christians—used to organize, describe, and evaluate narrative traditions.

Alex P. Jassen previews his new book exploring the diverse ways social contestation and violence was perceived and imagined by the Dead Sea Scrolls Sectarians.

The understanding that Jews engaged with a full sweep of Islamic sciences was arguably one of the earliest insights of modern Jewish historiography; indeed, medieval Jews were sometimes explicit about turning to non-Jewish sources. But scholarship has traditionally highlighted Jewish engagement with the larger world in fields other than law, such as poetry, theology, and linguistics. Building on the work of others, After Revelation recognizes that medieval Jews and Muslims structured their traditions in similar ways.

Power in the Name contributes to this growing body of work unbeholden to the myopic strictures of materialism and (more broadly) scientism by comparatively analyzing examples of humans changing their environment (e.g., healing or hurting others) by invoking powerful divine names.

“This book plunges us deep into the social relationships that made the production of rabbinic expertise possible. Weaving together accounts of tangible material support with sites of contact between rabbis and other people, I explore how rabbinic expertise was continually enacted and challenged through social interactions.”

“Cultural difference does not condemn us to incomprehension. It forces us to go beyond our own cultural horizons in an effort to make sense of what is going on in the world of others. Ancient historians must use the mindset of a cultural anthropologist, in addition to the traditional tools of their discipline.”

The exceptional influence and popularity enjoyed by DEH from late antiquity through the Middle Ages, and its critical interface with Jewish historiography as a work both based on and source of major Jewish histories, suggest that this work is important for scholars of pre-modern Judaism and/or Christianity to know.

Catherine Hezser and Constantin Willems introduce the AHRC-DFG Collaborative UK-German Research Project in the Humanities (2023-26) on Rabbinic Civil Law in the Context of Ancient Legal History.

“My work on the name-database has alerted me to the importance of corpora. I realize that most academics believe that their major contribution to world knowledge is their brilliant theses, in which they demolish the work of their predecessors and suggest new understandings of history and the sources that tell it. And indeed, theses are important and new thinking makes us think hard and keep history alive (albeit in a more “modern” or updated version). However, most theses, as brilliant as they may appear at the time they were composed, tend to have a short shelf-life.”

“I often think that scholarly understanding of the biblical Dead Sea Scrolls and I grew up together; over the years, and now decades, a paradigm shift has occurred in the field, and my own views have changed along with it.”

The books that were eventually included in the canon share “family resemblances” with other books left out of the canon. For instance, just as the same eye colour can be found in people belonging to unrelated families, so too the story of Israel is evident in canonical and non-canonical books.

“From my first book to my most recent, comparison (and its pitfalls), both within Judaism and without, has been a constant preoccupation as I continued to focus on texts of legal interpretation, and to struggle with how best to translate the rabbinic texts upon which I was commenting and to what extent either should inform or presume the other.”

Richard Kalmin offers a retrospective of his work on the historical analysis of Talmudic narratives.

Dr. Beth Berkowitz writes a retrospective of her first book, Execution and Invention: Death Penalty Discourse in Early Rabbinic and Christian Cultures (Oxford UP, 2006).

Erich Gruen with a retrospective of his work: “If a consistent thread runs through my studies of Jewish history in the context of classical antiquity, it can be found in resistance to the common portrayal of Jews as victims.”

For my part, I am satisfied that I have said what I can, and want, to say about this Gospel. Aside from my growing discomfort with John’s anti-Jewish language, I have gained much from my longstanding relationship with this Gospel, including a community of scholars whom I value and respect.

Seth Sanders shares how music, and in particular Yom Kippur liturgy, inspired his thinking about ancient texts.

Mira Balberg shares an unexpected influence upon her work with rabbinic literature.

The intellectual climate had changed, and I saw that I needed to situate my work as an historian in contemporary animal theorizing in order to be responsive to the interpretive richness of this new cultural moment in scholarship and to develop a vocabulary that might enable a reading “otherwise” of ancient Christian texts that feature animals.

Dr. Michael Swartz and Dr. Michael Satlow share a book that was an "unexpected influence" upon their academic work.

Beth Berkowitz and Ishay Rosen-Zvi share a book that was an "unexpected influence" upon their academic work.

Dr. Elizabeth Clark and Dr. Tal Ilan share a book that was an "unexpected influence" upon their academic work.

Find out which non-field related books Dr. Seth Schwartz and Dr. Steve Weitzman found influential.

Find out which non-field related books Dr. Adele Reinhartz and Dr. Andrew Jacobs found influential.