Ancient Jew Review is pleased to host this panel, first presented at SBL 2019 in San Diego as “ A Beginner's Guide to the Masorahs of Four Great Early Manuscripts as Represented in Recent Printed Editions.”

The Masorah of Biblia Hebraica Quinta (BHQ)

In the early middle ages, in order to preserve and protect the text of the Hebrew Bible that had been transmitted to them by both oral and written tradition, Hebrew scribes began to insert notes on the sides of Hebrew manuscripts indicating how words should be written. These scribes were known as Masoretes, the text they preserved is known as the Masoretic text, and the notes they wrote are collectively called the Masorah. The notes written on the sides of mss. are called Masorah parva (= Mp) notes, and those written at the upper and lower margins of mss. are known as Masorah magna (= Mm) notes. Each major manuscript has its own masorah, and its own sets of masoretic notes. One of the most important of these manuscripts that the Masoretes annotated was the Leningrad Codex, dated to 1008 C.E., that was rediscovered in the middle of the 19th century, and subsequently made the basis of the most widely used critical Hebrew Bible today, that of the Biblia Hebraica series. It is the intention of this article to compare how the two most recent editions in this Biblia Hebraica series, namely the earlier Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS),[1] and the newer Biblia Hebraica Quinta (BHQ)[2] deal with these masoretic notes.

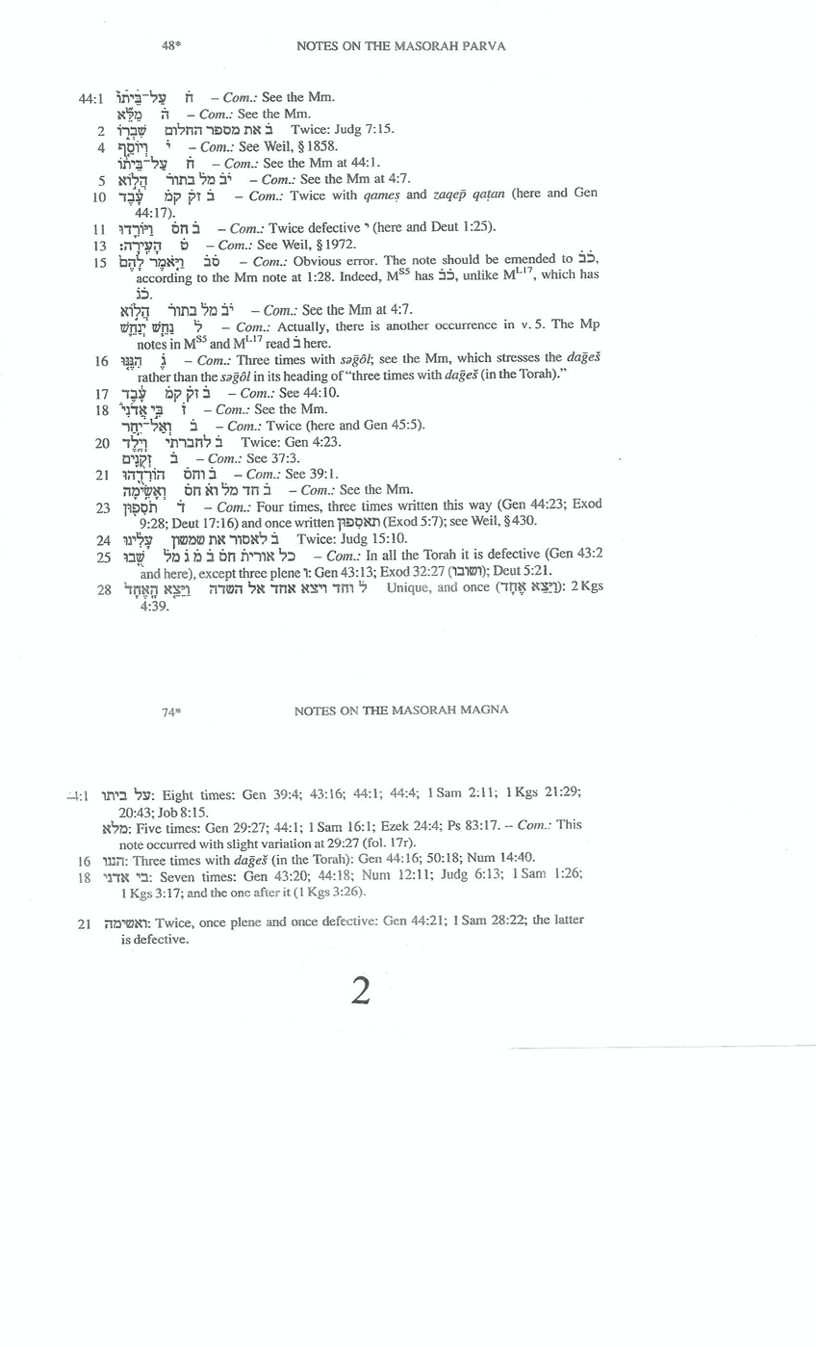

The Masorah of BHQ differs from that presented in BHS in four ways. In the first place, the text of the Masorah in BHQ is presented diplomatically, that is exactly the way it is in the underlying Leningrad manuscript. So, unlike Gérard Weil’s edited version in BHS, where Masorah notes were added, supplemented, and rearranged,[3] the Masorah notes in BHQ are a faithful representation of the notes in the manuscript, errors and all. Whatever is written in the manuscript is replicated in BHQ. Secondly, BHQ includes both the Masorah magna (Mm) notes as well as the Masorah parva (Mp) notes. BHS only includes the Mp notes on its pages although it does make reference to the Mm by means of numerical notations to Weil’s separately printed volume Masorah Gedolah,[4] which are keyed into a special apparatus underneath the Hebrew text. By contrast, BHQ, as you can see below, prints the text of the Masorah magna directly on the same page as its Hebrew text. The third difference between BHS and BHQ, as far as the Masorah is concerned, is that BHQ includes in its volumes a special section entitled “Notes on the Masorah parva” where many questions or problems connected with the Mp entries are discussed. Finally, the fourth major difference between BHS and BHQ is that BHQ provides a similar section of commentary for the Masorah magna entitled “Notes on the Masorah magna” where every Mm note is translated, all biblical references are provided, and where questions or problems in the notes are discussed.

In this paper, I shall survey briefly all four of these new features using for illustration purposes a sample page from the most recent printed BHQ fascicle, from the book of Genesis that was edited by Abraham Tal. The selection that is reproduced below is from Gen 44:15-26 that has to do with Joseph’s brothers in Egypt, and Judah’s appeal to Joseph for Benjamin’s release. In the image, you can see that the Mp notes are written alongside the Hebrew text on the right hand side of the page and that the Mm is printed underneath the Hebrew text just above the Critical Apparatus. These sections are also highlighted in the image on the right-hand side of the page.

We will start with the Mp notes. These are attached to words or phrases in the text that have little circles, called circelli (plural of circellus), over them. Thus in the first line of the text there is a circellus on the phrase וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם and that means it has a Mp note in the right margin. In the second line there are circelli on the phrases הֲלוֹא and נַחֵשׁ יְנַחֵשׁ and that means that there are Mp notes on these phrases given in the right margin. Similarly in the third line there is a circellus on the word נִּצְטַדָּק, and so there is the expected Mp note in the margin.

It must be admitted that reading Masoretic notes is not an easy job and takes time to figure out. The Masorah notes are presented elliptically, with abbreviations, and to complicate matters, to ensure that they do not inadvertently get mixed up with the Hebrew text, they are written in Aramaic.[5]In order to assist the average reader, the editors of BHQ have helpfully provided in the front every volume of BHQ a “Glossary of Common Terms in the Masorah Parva.” This Glossary is useful even for the more experienced Masorah student. When one looks at the Masorah notes on page one of the handout, it can readily be observed that most of them consist of Hebrew letters with dots on top, and these letters represent numbers according to the Hebrew alphabet. Thus the Hebrew ב̇ with a dot on it stands for “two”, ג̇ with a dot stands for “three”, ד̇ with a dot stands for “four,” and so on. The only exception to this system is the one number that is the most common of all Masoretic notes, that is, the number “one.” Curiously, the number one is not usually represented by the letter aleph, but instead represented by the letter ל̇ with a dot. This lamed is an abbreviation of the Aramaic wordלֵית “there is not,” that is, there is not another form like this, it is unique.[6] Examples of this ל̇ can be seen on the sample page in line two at v. 15 on the phrase נַחֵשׁ יְנַחֵשׁ, in line three at v. 16 on the form נִּצְטַדָּק , and in the middle of the page at v. 18 on the phrase כְּפַרְעֹה. The number “three” represented by the Hebrew ג̇ is found on the form הִנֶּנּוּ in the fourth line down on the page in v. 16. The number “two” represented by the Hebrew ב̇ is at v. 17 on the form עָבֶד, and the number “seven” represented by the Hebrew letter ז̇ “seven” is in v. 18 on the phrase בִּי אֲדֹנִי.

The vast majority of Masoretic notes are for purposes of protecting the correct writing of the text. In this regard a large number of notes have to do with orthography, whether a form has or has not matres lectiones, that is, waws or yods. The two most common terms used are מָלֵא “full” or “plene,” abbreviated as מל̇, to indicate that the word has either a ו or a י, and חָסֵר “lacking” or “defective”, abbreviated as חס̇, to indicate that the word does not have a ו or a י.

Examples of these notations are on the sample page. See the second note on the second line of the page at v. 15 on the form הֲלוֹא, which reads י̇ב̇ מל̇ בתור̇ “twelve times plene in the Torah,” that is, that the form הֲלוֹא occurs in the Torah twelve times written with a ו (and note as would be expected written without a waw which occurs seventeen times in the Torah). Or see the note on v. 21 on the form הוֹרִדֻהוּ which reads ב̇ וחס̇ “twice and defective”, that is, that the form הוֹרִדֻהוּ occurs twice without the expected י of the hiphil conjugation (הוֹרִידֻהוּ).[7]

Both מל̇ and חס̇ are found together at v. 21 on the word וְאָשִׂימָה , where the note reads: ב̇ חד מל̇ וא̇ חס̇ “twice, once plene, and once defective,” that is, that the form וְאָשִׂימָה occurs once with a י as written here, and once without a י as וְאָשִׂמָה in 1 Sam 28:22.

The Masorah also protects the writing of the correct vowels with appropriate accents. Thus in the note on עָבֶד “servant” in v. 17, the Masoretic note reads ב̇ זק̇ קמ̇ “twice the vowel (under the letter ayin) is a qameṣ (not the regular səḡôl) because of the zaqep̄ accent.” The regular form of “servant” in Hebrew is עֶבֶד. In pause, that is, in the middle of a verse with an ’aṯnaḥ accent, or at the end of a verse a sôp̄ pasûq, the səḡôl under the ayin (as is normal with segholate type nouns) is lengthened to a qameṣ.[8] But there are times, as this note indicates, that the vowel səḡôl under the ayin will also lengthen to a qameṣ, and that is when there is a zaqep̄ accent, hence the note ב̇ זק̇ קמ̇ “twice there is a qameṣ because of a zaqep̄.”

A special feature of the Mp is that instead of writing out the vowel as with qameṣ in the last example, the vowel can be placed under the letter indicating the number of occurrences. Thus in the note on הִנֶּנּוּ in v. 16, to indicate that this form occurs three times with a səḡôl (instead of a cəwâ) under the first nun, the vowel for the səḡôl is written under the ג̇, as גֶ̇.[9]

Masoretic notes are very useful for illustrating points of Hebrew grammar since there is always a reason why a word or phrase is selected for a note. Thus the Masoretic note on the phrase נַחֵשׁ יְנַחֵשׁ in v. 15 that it is unique (ל̇) is an opportunity to point out to students that the phrase the Masorah is noting is a piel infinitive absolute with a finite verb used to emphasize the verb “he (Joseph) can certainly divine (practice divination).” Or the note on the form תֹסִפוּן at v. 23 is an opportunity to point out that the Masoretes are noting a form of the verb with the so-called paragogic nun, as distinct from the regular form without this additional nun (תּוֹסִיפוּ).

Explanation and comments on these Mp notes are given in one of the great innovations of BHQ entitled “Notes on the Masorah Parva,” seen in the image below.[10] On the left side of the page is the chapter and verse starting on the page with chapter 44, verse 1, on the phrase עַל בֵּיתוֹ. The first note in this page that relates to our section is at verse 15 on the phrase וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם “he said to them” to which the Mp assigned the number ס̇ב̇ “sixty-two”, that is, that this phrase occurs sixty-two times in the Hebrew Bible. The Commentary notes that this number is an obvious error and that the note should be emended to כ̇ב̇, that is “twenty-two,” the number that is given elsewhere in the Codex, and this number “twenty-two” is the one that is found in another ancient Tiberian ms.

Another comment on a Mp in this verse is on the phrase נַחֵשׁ יְנַחֵשׁ on which there is an Mp note of ל, that is לית “unique.” The commentary says that actually there is another occurrence of this phrase in v. 5, and that the correct notation of “two” can be found in other early mss.

In verse 23 on the form תֹסִפוּן the Mp note reads ד, that is “four times,” and the editor comments that, of these four forms, three are written this way but a fourth is written slightly differently. All the biblical references for these four forms are given, as well as a reference to Weil’s Masorah Gedolah, where these four forms can be found listed in a Mm note. In verse 25 on the form שֻׁבוּ the editor translates the long Mp note “in all the Torah it is defective except three plene ו, and once again all the biblical references are given.

It is in the Mp notes where BHQ has introduced another innovation by recording doublet catchwords as they appear in the ms. The vast majority of doublets (forms that occur twice) are simply indicated by the letter ב. See for example at v. 18 on the formוְאַל־יִחַר, or at v. 20 on זְקֻנִים and there are many more on this page. The editor has indicated in most of these notes where the second reference occurs. However, there is another group of doublets where the Masorah actually indicates where the second verse occurs, and it does this by means of a catchword, a word that occurs in the second verse. These are called doublet catchwords and BHQ has presented for the first time to the scholarly public these doublet catchwords that were not published in the previous Biblia Hebraica editions (BHK[11] = BH3 or BHS). There are two such doublets in our section. One is in v. 20 on the form וְיֶלֶד. Here there is a Mp note ב that reads “twice” followed by the form לְחַבֻּרָתִי. This form לְחַבֻּרָתִי is a catchword indicating in which verse elsewhere in the Bible the form וְיֶלֶד, which is the subject of the note, can be found. It so happens that this catchword לְחַבֻּרָתִי comes from Gen 4:23 (which contains the boast of Lemech) and that is the verse where the second occurrence of וְיֶלֶד is found. Doublet catchwords thus serve to tie two texts together, and thus it is possible that they can be useful for biblical exegesis. Indeed these catchwords have been used for homiletical purposes by the 13th-14th century medieval Bible commentator Jacob ben Asher (1269-1343 also know as Baal Tur) in his commentary on the Torah.[12] Thus, with regard to the doublet וְיֶלֶד that occurs here and in Gen 4:23, from where the catchword לְחַבֻּרָתִי comes, ben Asher comments that the two occurrences of וְיֶלֶד here in our text וְיֶלֶד זְקֻנִים קָטָן “and a young child of his old age” and in Gen 4:23,כִּי אִישׁ הָרַגְתִּי לְפִצְעִי וְיֶלֶד לְחַבֻּרָתִ “for I have slain a man for wounding me, and a lad for bruising me” suggest that what Judah was saying : If I leave Benjamin in Egypt “I will have slain a man [e.g. Jacob, referred to as a man in 25:27 (אִישׁ תָּם “a mild man”)], and a child [e.g., Benjamin].” That is both Jacob and Benjamin would pass away, for they would be unable to exist, one without the other.

There is another set of doublet catchwords in our section, at v. 24 on the form עָלִינוּ. The catchwords there are לֶאֱסוֹר אֶת־שִׁמְשׁוֹן “to bind Samson” and they come from Judg 15:10 (where the Philistines want to capture Samson). See the image below. So the two texts, our text of Gen 44:24 and Judg 15:10 are thereby tied together. But what might the significance of this union be?

The catchwords from the book of Judges לֶאֱסוֹר אֶת־שִׁמְשׁוֹן “to arrest Samson” refer to the incident in the book of Judges when the Philistines came up to the Judeans to persuade them to arrest Samson. By providing these catchwords the Masoretes clearly believed that connecting these two texts had some exegetical significance. The precise significance is something we all can ponder. One possibility is the connection of “coming up with a request.” Jacob’s sons came up to their father in Canaan with a request to bring Benjamin down to Egypt, and the Philistines came up to the Judeans with a request to arrest Samson. I leave you to consider what other possible connections there might be between these two texts.

In the Notes on the Mp above you will no doubt have noticed that quite a few of the notes are those that refer the reader to the Mm where the note is explained in detail. The comment “see the Mm” may be seen on the top of the page on the notes in verses 1, 4, 5 and elsewhere on the page. And so this is a good time now to turn to the Mm the text of which you will find in the first image above. The location of the Mm in BHQ is always below the Hebrew text, though in the manuscript it can be found both above and below the text. One notices that, compared with there being seventeen Mp notes on the page, there are only three Mm notes, one on הִנֶּנּוּ in v. 16, one on. בִּי אֲדֹנִי in v. 18, and one on וְאָשִׂימָה in v. 21. This is a standard feature of all codices: there are many more Mp notes on a manuscript page since the Mp notes are short and can fit between either side the columns, whereas the Mm are of necessity longer, since they contain all the references. Thus each manuscript page will have many Mp notes but only a few selected Mm notes. On the actual ms. folio page where this section occurs there are forty Mp notes but only six Mm notes. The Mp notes may appear as many times as the lemma occurs in the manuscript, though there are no fixed rules. For example, The Mp note onתֹסִפוּן in v. 23 occurs at all four of its occurrences,[13] but the Mp note on בִּי אֲדֹנִי only occurs at five of its seven occurrences.[14] The Mm notes generally appear only once in a manuscript but occasionally they occur twice,[15] and sometimes three or more times.

On the second image above you will find the next great innovation of the BHQ entitled “Notes on the Masorah Magna” which provides a translation and commentary of the Mm. On this page the three Mm notes in our section are translated together with all the biblical references. The first Mm note in our section of text is on the phrase הִנֶּנּוּ in v. 16. The note is translated as “three times with dagesh” with the phrase “in the Torah” added in parentheses. The reason for this addition is because there is a slight difference of emphasis between the Mp and Mm with regard to the phrase הִנֶּנּוּ. Whereas the Mp notes the fact that the form הִנֶּנּוּ has a səḡôl under the first nun, the Mm emphasizes the occurrence of a daḡec in that nun. Because of this difference, it was necessary for the editor to add to the Mm note “in the Torah” because there is another form הִנֵּנוּ with a daḡec but not with a səḡôl at Job 38:35.[16]

Just as with the Mp, the Mm can be used as a great tool for classroom instruction. We can illustrate this by looking at the Mm note on בִּי אֲדֹנִי in v. 18. The Masorah comments on this phrase to contrast it with the parallel phrase בִּי אֲדֹנָי that occurs four times.[17] The phrase בִּי אֲדֹנִי, always used from a litigant to a superior, occurs seven times in the Hebrew Bible, and in the first image, the Mm gives the references by means of a few identifying catchwords in each verse separated by dots. All the biblical references by book, chapter and verse are given in the Notes on the Mm in the second image, and presented again in the last images. The first set of identifying words וַיֹּאמְרוּ בִּי אֲדֹנִי comes from Gen 43:20 on an earlier occasion when Joseph’s brothers address Joseph’s overseer when they were attempting to explain about the return of their money in their sacks. The second set of identifying words is וַיִּגַּשׁ אֵלָיו יְהוּדָה וַיֹּאמֶר comes from Gen 44:18 which is the sample text that we have been using, and the context is Judah’s plea to Joseph for the release of Benjamin who has just been implicated in stealing Joseph’s silver goblet. The third set of catchwords come from Num 12:11 וַיֹּאמֶר אַהֲרֹן אֶל־מֹשֶׁה “and Aaron said unto Moses” and occur in the context of Aaron’s plea to Moses on behalf of his sister Miriam who was just smitten with a skin affliction (the biblical leprosy) for speaking ill of Moses. The fourth set comes from Judg 6:13 וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלָיו גִּדְעוֹן and appears in the context of Gideon’s complaint to the angel of the Lord (מַלְאַךְ יְהוָה) about Israel being abandoned into the hands of the Midianites. The fifth set of identifying words comes from 1 Sam 1:26 וַתֹּאמֶר בִּי אֲדֹנִי חֵי נַפְשְׁךָ at the beginning of the book of Samuel when Hannah brings her young son Samuel to the Temple in fulfillment of her vow. The final two sets of identifying words are of special interest because they may help solve a literary problem in the text. The two sets of words both come from the third chapter of 1 Kings in the famous story of Solomon and the two harlots where, as a demonstration of his great wisdom, Solomon suggests cutting up the live baby claimed by each of the harlots. The literary problem is this: nowhere in the text of this story is the true mother named. We don’t know if the true mother is the first litigant or the second one. However, the Masoretic note may provide a clue since the phrase בִּי אֲדֹנִי is said by the first litigant in v. 17 and is also said by the true mother in v. 26. Since both speakers use the same phrase, it is very likely (though it is not conclusive) that the first speaker, the first litigant is the true mother. So this is an example of how Masorah magna notes might be used in elucidation of biblical text problems.

In conclusion, I have given some examples of how the Masorah can enhance our biblical studies and how BHQ, by means of its exceptional presentation of the Masorah both on its text page and in its Masorah commentaries, has contributed greatly to the enhancement of Masoretic studies.

[1]Karl Elliger and Wilhelm Rudolph, eds. Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. 5th rev. ed. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1997.

[2]A. Schenker, et al. Biblia Hebraica Quinta. Stuttgart: Deutsche Biblelgesellschaft, 2004-

[3]See Weil’s own account of his additions in the “Prolegomena” pages xiv-xix in BHS.

[4]Gérard E.Weil, Massorah Gedolah. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Press, 1971.

[5]We note that Hebrew and Aramaic words interchange in these notes. For example, an abbreviation of the Hebrew תּוֹרָה “Torah” occurs in line two at v. 15 on the form הֲלוֹא . The note reads י̇ב̇ מל̇ בתור̇ “twelve times plene in the Torah,” that is, that the form הֲלוֹא occurs twelve times in the Torah written with a ו in contrast to the seventeen times when it is written without this ו in the Torah. The Aramaic equivalent אוֹרַיְתָא “The Torah” is found in its abbreviated form at verse 25 on the form שֻׁבוּ at the beginning of the Masoretic note כל אורית̇ חס̇ “defective in the entire Torah,” that is, that the form שֻׁבוּ is written this way in the Torah without an intermediate ו. The note goes on to say that there are, however, three exceptions when the form is written with this intermediate ו (Gen 43:13; Exod 33:27 וְשׁוּבוּ] ]; Deut 5:21).

[6]Though א is occasionally used also to indicate “one” as in the Mp note on וְאָשִׂימָה at v. 21.

[7]E.g., לְהוֹרִיד (Gen 37:25); הוֹרִידוּ (Gen 43:7); וְהוֹרִידוּ (Gen 43:11(..

[8]Thus with an ’aṯnaḥ accent at Judg 9:30; 1 Kgs 9:22; Prov 29:19, and with a sôp̄ pasûq at Lev 25:39; 25:42.

[9]The purpose of the note is to show that the form הִנֶּנּוּ is written three times with a səḡôl as distinct from its occurrence four times with a cəwâ (הנְנו) [Josh 9:24; 2 Sam 5:1; Jer 3:22; Ezra 8:15].You will note that the Commentary on this form points out that the Mm stresses the fact that this form has a daḡec in the first nun instead of emphasizing, like the Mp, the fact that there is a səḡôl under this nun.

[10]Not all Mp notes accompanying the text are commented on in the “Notes” section. The reason for this is an editorial one as set forth in the guidelines by the Editorial Committee of BHQ. Where lemmas can be explained by simply resorting to the “Glossary of Common Terms” there is no need to comment on them in the Notes section. So there is no comment on the lemmas נִּצְטַדָּק in v. 16 or on כְּפַרְעֹה in v. 18 since both of these forms only occur once, and are indicated by ל̇ “unique” Mp notes. Likewise, if a lemma can be easily found in a standard Hebrew concordance such as Even Shoshan (Abraham, Even Shoshan, A New Concordance of the Bible. Jerusalem: Kiryat Sefer, 1993) then there is no need to comment on the lemma nor give its references. Such a case is with the lemma אֲהֵבוֹ in v. 20 which occurs four times and these four references are easily found in Even Shoshan.

[11]Rudolf, Kittel, ed. Biblia Hebraica. Stuttgart: Württembergische Bibelanstalt, 1937.

[12]Ben Asher’s commentary on the Torah has recently been published with an English translation and notations by Avie Gold, Baal Haturim Chumash (5 vols; Brooklyn, New York: Mesorah, 1999-2004).

[13]At Gen 44:23; Exod 5:7; 9:28; Deut 17:16.

[14]At Gen 43:20; 44:18; Num 12:11; Judg 6:13; 1 Kgs 3:17.

[15]As is the case with בִּי אֲדֹנִי, here at Gen 44:18 and at 1 Kgs 3:17.

[16]The other occurrences of הִנְנוּ without a daḡec or səḡôl are at Josh 9:24; 2 Sam 5:1; Jer 3:22; and Ezra 9:15.

[17]At Exod 4:10; 4:13; Josh 7:8; and Judg 6:15.

David Marcus is a professor of Bible and Masorah at the Jewish Theological Seminar of America.